It happened again! I love it when my interests align.

Not too long ago, Veritasium released a fascinating video on the physics of rainbows—which you should totally watch. In that video they discuss the mechanics of how light waves of differing wavelengths refract in water droplets to form various kinds of single and double-banded rainbows. The video is a pitch to get the viewer to question their prior knowledge of how rainbows work and then it uses that question to dive in to the deeper physics of light that explain an otherwise common phenomenon.

What I didn't expect to find, was that rainbows are not just interesting mechanistically, but that they were a particularly insightful topic of discussion for medieval scholastics when debating the importance of scientific experimentation itself!

Beware, we're going deep into the weeds!

The Issue of Experiment

In order for this to make any sense, we need to dive a bit into how ancient and medieval peoples (and some modern historians thereof) understood their world.

Medieval scholars were not idiots, as some might sometimes conceive today. They had a very nuanced and complex way of understanding and classifying the natural world. The trouble is that it is a very different method of understanding than we use today and that can be very confusing for us moderns to understand. Particularly we have to consider the role of experimentation in ancient and medieval natural philosophy, which was heavily influenced by Aristotle (aka the Stagirite).

I think this quote from Dr. Peter Dear sums the prevalent understanding up pretty well:

"For Aristotelians, by contrast, the philosopher learned to understand nature by observing and contemplating its

ordinary course,not by interfering with that course and thereby corrupting it."– Promethean Ambitions, William Newman. p 240 Footnote 8. A quote by Peter Dear from Revolutionnizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and its Ambitions

Now, you might ask yourself: why did they think this way? What reason could the ancients and medievals have for such a strange seeming conclusion? Well, consider this quote from Antonio Perez-Ramos.

"What is the point...of making or constructing something in order to gain insight into Nature's mysteries if we posit from the very start that no productions of human technology can remotely equal or even approach the essence and subtlety of natural processes?"

– Promethean Ambitions, William Newman. p 241 Footnote 9. A quote by Antonio Perez-Ramos from Bacon's Forms and the Maker's Knowledge (Emphasis mine).

This assumption, made axiomatically for centuries, is critical if one is to understand this branch of ancient and medieval theory. And while it is true that not all scholars of the time believed such things (as we will see) it is true for many. As such it is/was a prevalent view in the works of many historians as well, a phenomenon that Dr. William Newman calls the noninterventionist fallacy.

The noninterventionist fallacy [is the idea] that the Stagirite and his followers were fundamentally nonexperimental or even actively opposed to experiment, because experimentation involved intervention in natural processes… Indeed, in [this] view, avoidance of artificial intervention was a necessary consequence of the Aristotelian conception of natural science. Since Aristotle defined an object's "nature" as the sum of its regularly occurring properties, any attempt to isolate the object from its normal environment could only interfere with its nature. Since experiment relies on precisely such interference… it becomes ipso facto useless in Aristotelian natural science.1

- Promethean Ambitions, William Newman. p 238-240 (Emphasis mine).

However Newman argues that this fallacy is just that: a fallacy, and that his colleagues (historians of science) should not interpret all medieval or ancient sources this way precisely because Aristotle himself didn't follow the noninterventionist mold, and neither did a very studious set of his later disciples.

The Solution in Rainbows

One of the examples of ancient and medievalist scientific experimentation comes to us from the writings of Aristotle himself and his later followers.

Aristotle wrote extensively about how rainbows could be formed by the splash and spray of an oar, and later writers like Albertus Magnus and Robert Bacon experimented with making rainbows from glass vessels, spray, wet rags, and more. Albertus "used vessels filled with water to replicate the individual drops of water in a rainbow," and a wet rag to "produce a fine mist and the attendant spectrum."2 Albertus then proceeds to replicate Aristotle's experiments with the oar.

However the culmination of the experimentation on this topic has to be the work of Theodoric of Freiburg who wrote in the first decades of the fourteenth century.

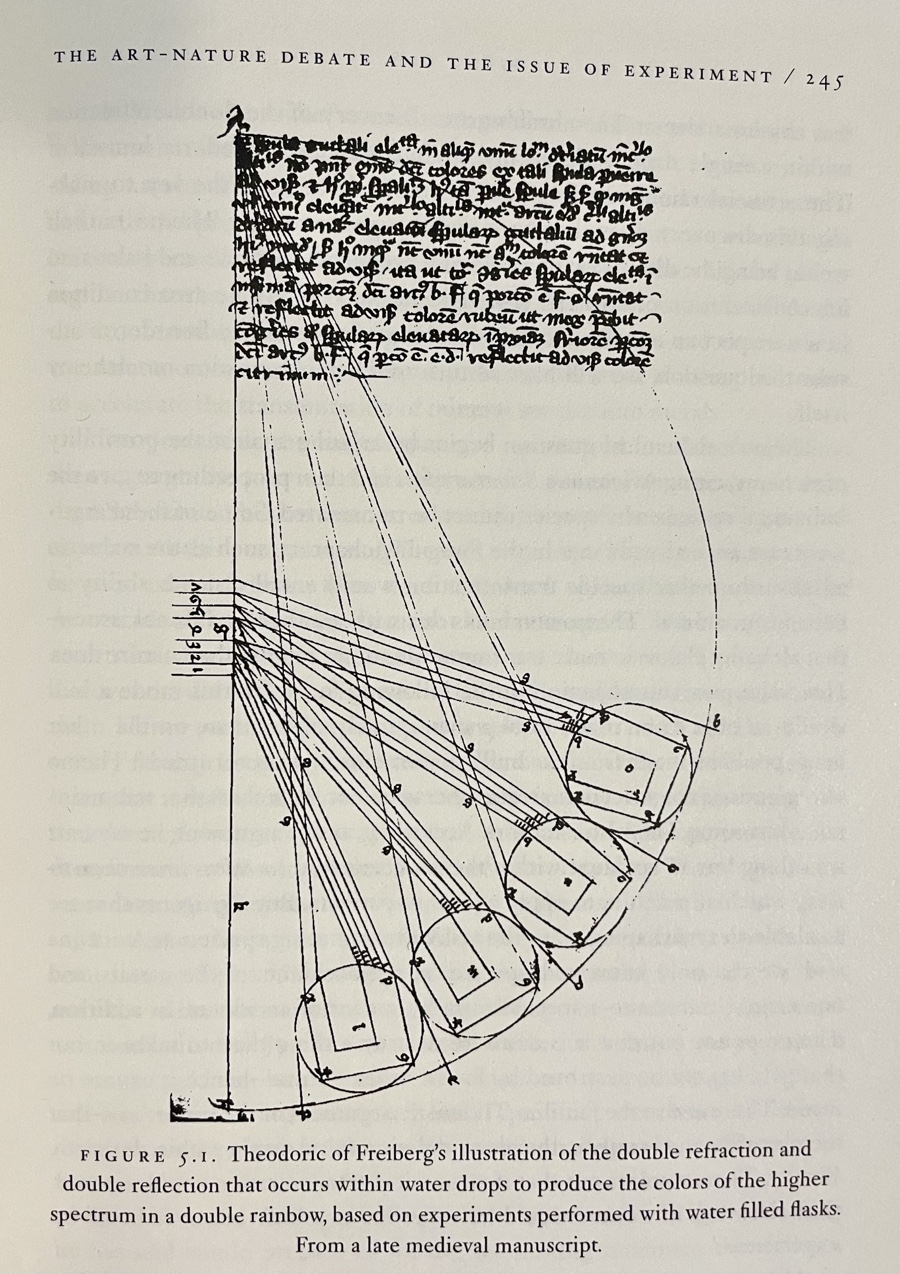

Theodoric managed to use the experimental techniques that we have already described to prove that the rainbow came about from a double refraction and a single reflection within each drop of water. He even managed to explain the formation of the common secondary bow in terms of a double refraction and a double reflection (fig 5.1).

- Promethean Ambitions, William Newman. p 244

What's more, this idea that all Aristotelian natural philosophers denied the usefulness of experiment is refuted by none other than a medieval scholar himself, Themo Judaei when discussing the merits of scientific experimentation and its regard to rainbows and their accompanying halos.

Likewise it must be known that it is said in the title of the question: "just as the rainbow or halo etc.," because it is difficult to know well the composition or manner of composing metals, just as it is difficult to know the way of generating the rainbow. And unless we knew how to make or see the rainbow and its color, as well the halo, by means of art, we would hardly be led to an understanding of the rainbow or the halo—and how they come to be thus.3

Quaestiones, Themo Judaei. Question 27.

He goes on to discuss the relevance of this knowledge to experimentation via a chemical method of making gold, but that is another story.4

2 Newman, P 244.

3 "Art" here means the artificial making of things in any way, not just, like, painting—though painting is indeed a kind of art in this definition.

4 While chemically impossible, need I remind you, we can actually do this today so I think the point remains quite valid.