History as a subject is often viewed by students and the public at large as a domain without a use, a pedantic study of dates and names with some vague mission to remember the past—a memorial to ages past but neither a forward-looking or useful endeavor. The study of history produces teachers of history and nothing more. And while the study of history does not produce new widgets or novel computer advances, and nor does it deepen our understanding of materials science or physics.

The humanities, in which history and studies of language and culture are a part, are not there to improve our understanding of nature or develop technology, they exist to improve the minds (both cultural and individual) of the people we are.

History doesn't improve our world, it improves us. It gives us context for the world we live in and it helps us understand the reason why things are as they are and learn from the people before us.

History as Context

Imagine waking up every day with no memory of the day before, no idea who owned the house you slept in, no idea what country you're in, and no idea why everyone around you speaks the languages they do.

Living in such a world would be disorienting, confusing, non-sensical. Yet this is the world without history. The world without history just is. It isn't a work in progress, but a finished piece—one that lives and dies with you—and has no meaning beyond the present moment.

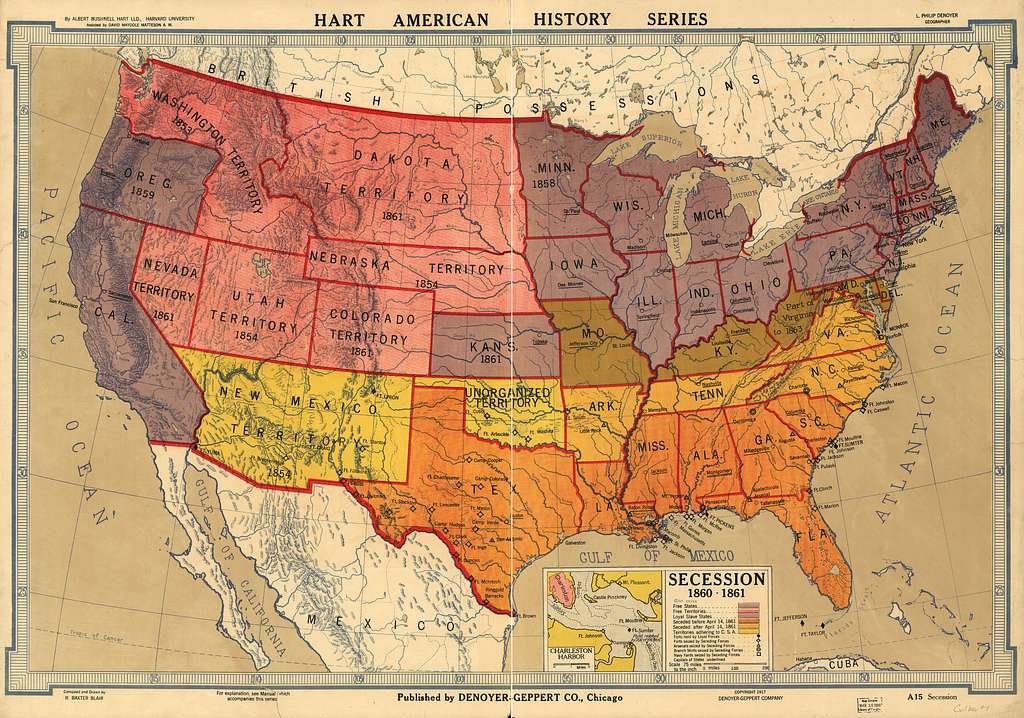

History doesn't let us predict the future, but it can be an enormous help in explaining the present. Current events are utterly indecipherable without the context of history and within that context, they feel less and less apart. Indeed our recent past of the Post-War Order is the oddity in history, and a real thing to be cherished and seen as something fleeting, fragile, and truly precious.

Yet without the context of history, we're blind to the reality that we live in a world truly set apart from everything that's come before and one that's deeply connected and familiar to the worlds of the past. That context is important because it gives us the vision to see the world that could be, both the paths of dark and of light that are set before us. It shows us who we are.

History as Memory

Living Memory is the collective memory of everyone alive in our society today. It is ever-changing and ever-fleeting. We remember the 2008 Financial Crisis quite well, but our memory of World War 2 is all but gone now. We read about it, sure, but our collective living memory of it has diminished and with that lapsing has gone all the memory of precisely why the world is ordered the way it is. This is not a value judgement, it is a statement of fact.

In a couple recent posts, I describe how I try to use writing by hand as a way to increase my understanding of myself and my own memory. This is a form of personal history, and I find it difficult to express how much doing so has helped me better understand myself and my own thoughts.

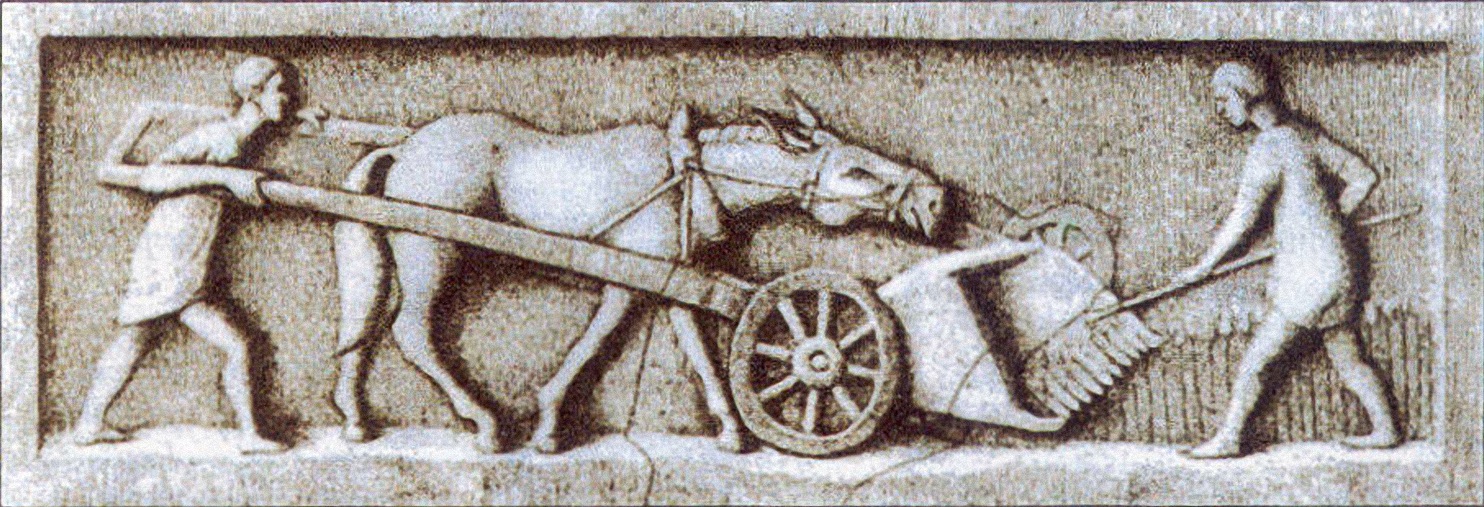

This is analogous to our collective history. Though it's important to remember that history is not the act of writing, but the act of looking back and analyzing what was written. We write so that we can remember. We cannot learn from our mistakes if we refuse to write them down, or worse, if we refuse to look back.

The context of history is terrible and it is beautiful. It is the greatest story ever told with myriad heroes and villans, tragedy and triumph, love and grief all endlessly shifting in and out of view. And it was made (and is being made) by people no different than ourselves. Most of them didn't have the luxury to place themselves within the broader historical narrative. We do. Let's not ignore so precious a gift.