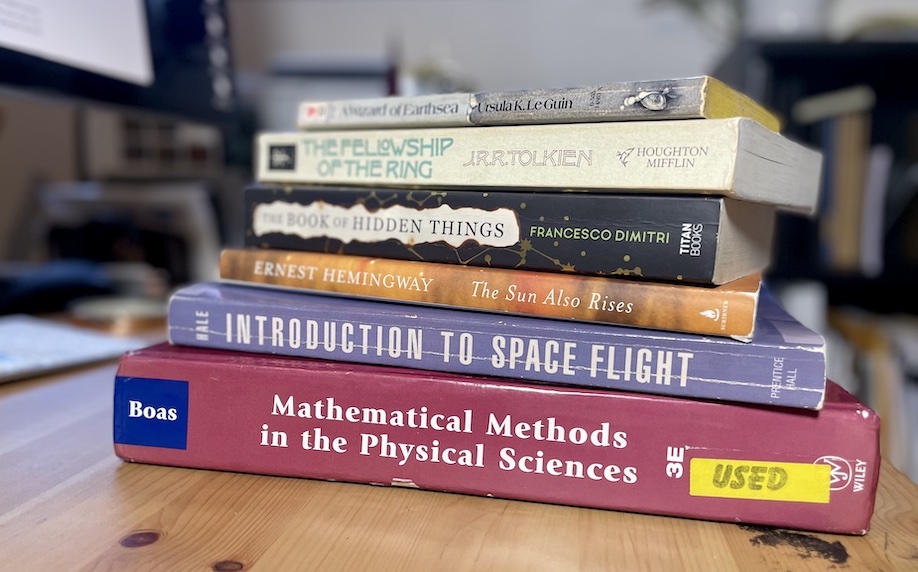

I love reading and watching non-fiction because it never answers a question without raising many more. The process of learning and discovery is a never ending quest to slay the hydra. Every severed head—every answered question—only brings with it more heads to slay. This all brings me to an insight that occurred to me the other day after rewatching a Veritasium video on the discovery of the Principle of Least Action—for like the fifteenth time.

Perhaps narrative structures, stories, also obey this same principle.

Action, Briefly Explained

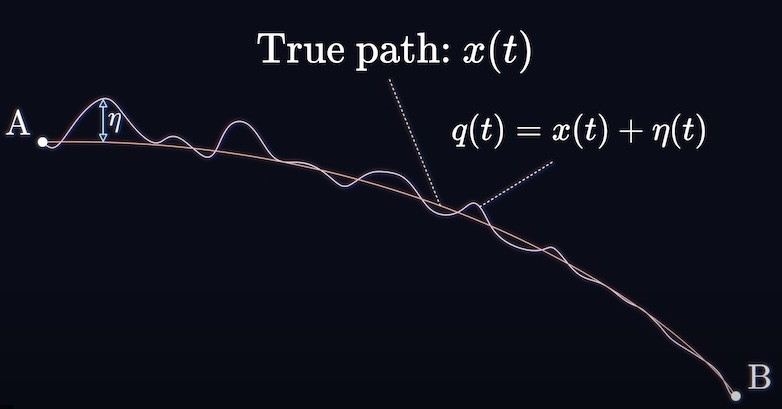

For those who don't know about the Principle of Least Action, you should watch the video—it's great. But in short, Action is a concept in physics. Specifically, it's the combination of mass, distance, and velocity, the minimization of which seems to underpin the motion of all objects in the universe. Action alone seems to determine the trajectory of objects in space, that is the path they take as they move.1 In our modern theories of physics Action is fundamental, and Nature seems to do her best to minimize the expense of it.

Of all the possible paths that an object could take as it moves, it seems that objects in free-fall motion always move along the specific trajectory which minimizes the Action.

Narration viewed as Action

In writing there is a principle called Chekhov's gun, which states simply that:

If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don't put it there.

The point is to rid your story of extraneous elements. Detail must serve a narrative purpose; it must be justified. In a way, this is similar to the Principle of Parsimony (a.k.a. Occam's Razor) which is commonly paraphrased as, "of two competing theories, the simpler explanation of an entity is to be preferred." As a writer, your job is to craft a world and a narrative that fits disparate information together into a seamless whole. The better story is the one which requires fewer assumptions by the reader and omits extraneous information. This might be otherwise phrased as crafting a "tight" story. A tight story with a good ending is one that minimizes the information required for a reader to find the narrative and its completion engaging, one that ties up loose ends, and one that gives the reader the feeling of satisfaction and closure.

Stories exist in an abstract space with many more dimensions than our familiar 3-D space would allow me to depict. However the story is still singular, it follows a well-defined path traced by its words through this space and my argument is that the "ideal path", the one which the author ought to prefer when writing, is the one which minimizes the Action in that space.

To be clear, I do not have a rigorous formulation for this idea, it's an idle musing after all, but upon reflection it seems to comport with my intuition about good writing. Perhaps a thought experiment will help.

A (Totally Rigorous) Proof

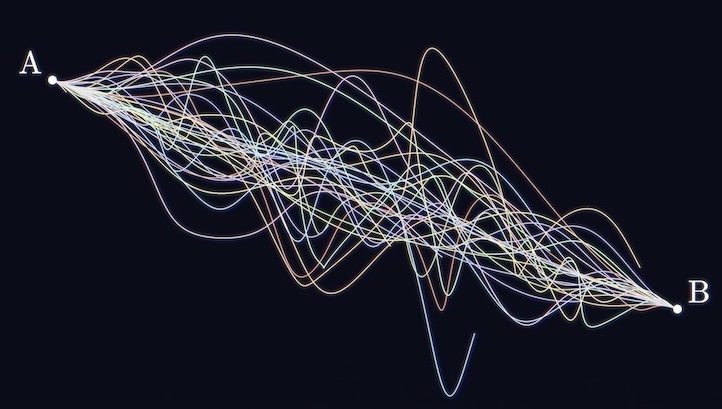

Consider two points on the Plane with the X & Y dimensions quantifying some range of values for narrative structure: say the amount of world-building in a scene vs the progression of the story over all. Moving "up" on this chart means adding more backstory, while moving "right" is progressing the story.

Now, the story will likely have many, many more dimensions than this, but stay with me.

The story itself then is a curve which connects the two points at a given page count. This curve, or the path of the story as it moves through pages, can take many forms. However the one it should take under the principle above is the one which minimizes the Narrative Action (which we have not, and will not, formally define).2

Now consider altering this curve by adding additional detail about the world. This detail is by definition unnecessary to the story because the minimal path exists from point A to point B as defined above. Therefore that detail would only increase the total Narrative Action and should be removed.3

In this way, the writer should emulate Nature in her effort to minimize all information in their story which is not required to attain the desired effect. Obviously the hard part is actually intuiting the true path that does this, but I'm not here to tell you how to be a good writer, that's too hard. Still, these ideas do seem connected, or perhaps that's just me.

1. Yes, curvature is also a thing. Also Quantum. Ignore it.

2. Out of scope for this conversation.

3. Associated with this is the idea that a story should create stresses, that is ask questions, which are relaxed or resolved by later sections. That tension is critical, but the path followed from the author's insertion of that tension (akin to the throwing of a ball which disturbs it from free-fall motion) and the resolution of it (the ball's final destination) should still follow this principle.